Well today, for our usual appointment with the Movie taleswe will jump back in time to the ninetiesthat is, in the mid-nineties, reviewing Time to kill (A Time to Kill), opus signed by the late Joel Schumacher (Lost boys, 8MM).

Film from 1996 of the full-bodied, perhaps prolix and excessive, lasting exactly two hours and twenty-six minutes, Time to kill was written by Academy Award winner Akiva Goldsman (A Beautiful Mind), former collaborator e screenwriters for Schumacher. Who, summarily and with many licenses, adapted for the big screen a famous and appreciated book by the master par excellence of the legal thrillersaka John Grisham. Who, moreover, made his debut in the literary field with his novel of the same name.

Schumacher, later The clientalso the latter taken from a book by the famous and just mentioned expert of courtrooms in the especially “editorial” field, already numerous times transposed for various and equally famous film adaptations (The Rain Man, The partner, The jury), therefore he tried his hand again with a convoluted and lawful procedural affair with a high adrenaline rate, full of unsettling and exciting unexpected twists, vividly imbued with strong pathos And suspense in abundance, even filled with exhausting exaggerated rhetoric and heavy Manichean captioning bordering on presentable, as well as, moreover and pertinently, we will enunciate and explain later, providing you with more and more painstaking reviewer and exegetical details delineating, we hope, meticulously faultless. Having said that, let us also state that Time to killalthough at the time it was mostly widely panned by a lot of critical intelligentsia, especially our own, it is not contemptible as most said and, while certainly not shining in originality and seriously lacking in many respects, especially as regards its writing, often predictable and schematic, revised today, with more prudence and measure, equally has many appreciable and decidedly noteworthy moments.

Transcribing, below, the synopsis from IMDbin this case correct and not requiring further superfluous explanations, here is the synthesized and reported plot:

In Canton, a fearless young lawyer and his assistant defend a black man accused of killing two white men who raped his 10-year-old daughter, inciting violence and revenge by the Ku Klux Klan.

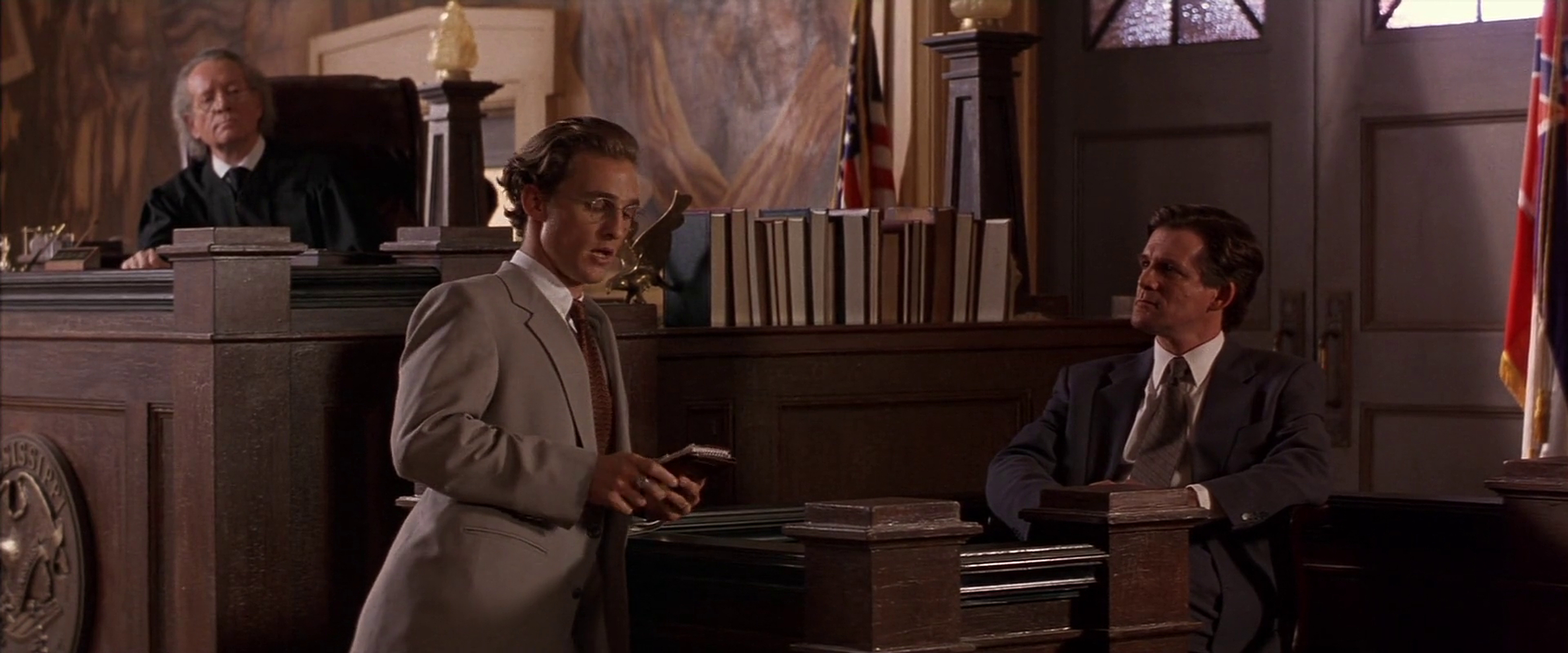

The black man is called Carl Lee Hailey and, regardless of the debatable qualitative value of this film examined therein, he is interpreted with undoubted skill by the usually excellent Samuel L. Jackson who, for this warmly felt interpretation of his, was rightly nominated for the Golden Globes for best supporting actor, while his defense attorney, young, ambitious and tough, strong-willed, unscrupulous and unyielding, is embodied with just as much acting vigor by an excellent Matthew McConaughey. Who, although uncertain at times, still a little immature, therefore here and there dazed and slightly bewildered, awkward at the beginning, pomaded and wearing a tie, often exhibiting pleased poses, impeccably photogenic, at the same time shows off a surprising grit, in many situations, passionate and enthralling.

Not least, compared to the two main interpreters mentioned, is the very rich parterres actor perfectly directed and orchestrated by Schumacher, among which stands out, as usual, a slimy Kevin Spacey, the beautiful Sandra Bullock in the role of the student who helps the character of McConaughey in the investigation, the dazzling appearance of Ashley Judd, Octavia Spencer, Oliver Platt (old acquaintance of Schumacher since Deadline), Charles S. Dutton, Brenda Fricker, Patrick McGoohan, Chris Cooper, and the well-matched father and son pairing, made up of Donald and Kiefer Sutherland (regulars and former dearest friend and actor among Schumacher’s favorites), this time deployed on fronts opposites.

Packaging, as they say, luxurious and perfect on a formal level, with excellent photography by Peter Menzies Jr., somewhat pompous music by Elliot Goldenthal for a film accused, as often happened with Schumacher’s films, of justice more self-righteously ambiguous and unhealthily reactionary.

On closer inspection, however, neglecting the structure, in fact and as I have already said, unbearably rhetorical in too many passages, including the climax ending that obviously we will not reveal if you are among those who have never seen this film yet, Time to killdespite being classified among the Hollywood films with a fairly obvious canvas, despite being built according to the classic style “mainstream” of the most abused and conventional (the Americans define films like this with the expression formulaic), despite many jokes and beatings and answering phone calls, it captivates and excites, keeping us in suspense from the first to the very last minute.

Merit of an extremely professional and shrewd direction which, while not being transcendental and, we repeat, not showing us anything particularly original and/or innovative, with an appreciable consolidated craft knows how to keep up with the narrative rhythm with kinematic experience, if not learnable, at least not negligible .

When Paolo Mereghetti, in his Dictionary of Films, trivially defined Time to kill an amateur mega-meatloaf fork maker, superficially snubbing McConaughey’s test, describing it in these hasty, unflattering terms, or rather a protagonist concerned only with looking now like Paul Newman and now like Marlon Brando, for which he dismissed him and classified him as a mediocre actor, Mereghetti was extremely hasty and not very wise. In fact, time, as inexorably merciless as it is less hastily sententious than Mereghetti and more equitable, fortunately generous and revealing, as we know, decreed the by now unappealable final verdict according to which, the mistreated and for too long unjustly underestimated McConaughey, after his sensational performance superlatives, especially in Dallas Buyers Club & True Detectiveshould not and can never again be taken lightly in such an ungrateful and foolishly disarming way.

Finally, to conclude, we add the following, we believe, very interesting curiosity: the actor Anthony Heald, after having been the psychiatrist Dr. Frederick Chilton in The silence of the lambshere plays a similar almost equal role, that is the psychiatric director of a mental asylum called to testify on the stand regarding an alleged and perhaps erroneous, misdiagnosed mental illness…

Post Views: 73