Rick Jaenisch underwent six treatments before being cured of hepatitis C in 2017. Each time his doctor recommended a different combination of drugs, his insurance company denied the initial request and then ultimately approved it. This sometimes delayed his care for months, even after he developed end-stage liver disease and was awaiting a liver transplant.

“By then, treatments should be readily available,” said Jaenisch, 37, director of outreach and education at the Open Biopharmaceutical Research and Training Institute, a nonprofit in Carlsbad, California. “I’m the best person for treatment.”

But it won’t be easy. Jaenisch was diagnosed in 1999 at age 12 when his father took him to a hospital in San Diego after Jaenisch showed him that his urine was brown, indicating there was blood in it. Doctors determined he likely contracted the disease from his mother at birth. His mother, a former dental surgical assistant, learned she had the virus only after her son was diagnosed.

People infected with this viral disease, which is usually spread through blood contact, often appear to be doing well for many years. An estimated 40% of the more than 2 million people infected in the United States don’t even know they have the virus, and the virus may be quietly damaging their livers, leading to scarring, liver failure or liver cancer.

With several highly effective, low-cost treatments now on the market, one might expect that nearly everyone who knows they have hepatitis C will be cured. But a study published in June by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that was far from the case. The Biden administration’s proposal to eliminate the disease within five years aims to change that.

Overall, the agency’s analysis found that in the decade after new antiviral treatments were introduced, only about one-third of people initially diagnosed with hepatitis C cleared the virus through treatment or the virus resolved on its own. Most people who are infected have some type of health insurance, whether it’s Medicare, Medicaid or commercial insurance. But even among commercially insured patients who were most likely to receive treatment, only half of those 60 or older had cleared the virus by the end of the study period in 2022.

Carl Schmid, executive director of HIV+ Hepatitis Policy, said: “Unlike HIV, where you have HIV for the rest of your life, it takes as little as eight to 12 weeks and you’re cured.” Institute. “So why don’t we do better?”

Experts point to several obstacles faced by those infected. When new treatments are introduced, cost is an important factor. Private plans and state Medicaid programs limit spending on expensive drugs, including restrictions that make it harder to obtain them, impose prior authorization requirements, limit use to people with already damaged livers, or require patients to abstain from drugs to qualify.

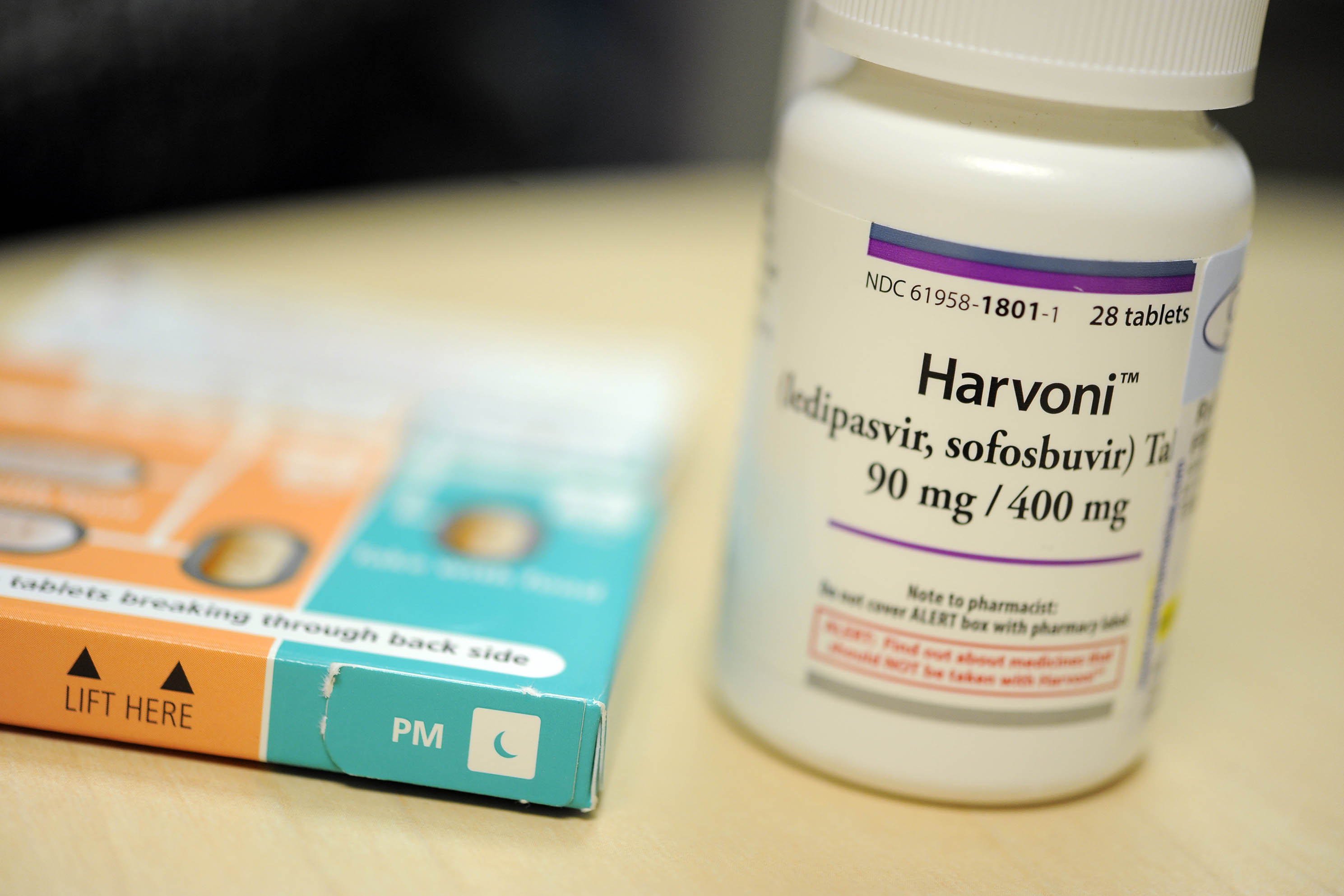

When Jaenisch’s case was cured at age 31, the landscape of hepatitis C treatment had changed dramatically. In 2013, a breakthrough once-daily pill became available, replacing a grueling regimen of weekly interferon injections that had uncertain success rates and serious side effects. The first “direct-acting antiviral drug” treated the disease in 8 to 12 weeks with few side effects and a cure rate of over 95%. As more drugs are approved, the initially eye-popping $84,000 price for a course of treatment has gradually dropped to about $20,000.

As drug prices fall, many states, under pressure from advocates and public health experts, have removed some of the barriers that make it difficult for treatments to get approved.

There are many more barriers that have nothing to do with drug prices.

Ronni Marks is a former hepatitis C patient who advocates for patients who are often overlooked. These include rural residents and those who are uninsured, transgender or injecting drug users. An estimated 13 percent of people entering and leaving U.S. jails and prisons each year have chronic hepatitis C infection, but access to care there is limited.

Marks said many vulnerable people need help accessing services. “In many cases, they can’t travel, or they can’t get tested,” she said.

Unlike the federal Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, which for more than three decades has provided grants to cities, states and community groups to provide drugs, treatment and follow-up care to people living with HIV, there has been no coordinated, comprehensive Program Hepatitis C Patient Program.

“In a perfect world, this would be a great model to replicate,” said Sonia Canzater, senior program director of the Infectious Diseases Initiative at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law in Georgetown. “That may never happen. What we would most like to have is this national program that systematically provides access so that people are not beholden to the policies of their state.”

The national plan Kanzate was referring to is a $12.3 billion, five-year plan to eliminate hepatitis C that is included in President Joe Biden’s fiscal 2024 budget proposal. Francis Collins, the former director of the National Institutes of Health, is a leading advocate in the Biden administration.

The program will:

- Expedite approval of point-of-care diagnostic tests that enable patients to be screened and begin treatment in a single visit, rather than the current multi-step process.

- Improve access to medicines for vulnerable populations, such as those who are uninsured, incarcerated, part of Medicaid or members of American Indians and Alaska Natives, through the use of subscription models. This approach, known as the Netflix model, enables governments to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies to establish a fee that will cover the cost of treatment for all individuals in those groups who need it.

- Build public health infrastructure to educate, identify, and treat people with hepatitis C, including supporting universal screening; expand testing, provider training, and additional support for care coordination; and connect people to services.

“This is as much about compassion as it is about good financial sense,” Collins said, pointing to an analysis by Harvard University researchers that predicted the plan would prevent 24,000 deaths and save $18.1 billion in health care over 10 years. expenditure.

Collins said legislation to implement Biden’s plan, currently in draft form, is expected to be introduced when Congress reconvenes after its summer recess. The Congressional Budget Office has not yet estimated its cost.

Before the 2020 covid-19 outbreak, hepatitis C killed more Americans each year (nearly 20,000) than any other infectious disease. Supporters are glad the virus is finally getting the attention they think it deserves. Still, they don’t believe Congress will support more than $5 billion in new funding. The remainder will be provided in the form of savings from existing plans. But, they say, it’s a step in the right direction.

“I’m excited” there is a federal proposal to end hepatitis C, said Lorren Sandt, executive director of the nonprofit Ambassadors of Care in Oregon City, Ore. “I’m so excited” I’ve cried with joy so many times since this movie came out. “