TErence Davis was 45 years old when he began making his first large-scale film. Distant voices (1988) in the Kensington area of his native Liverpool. In an industry like film, which reveres youthful precociousness and precocious talents like handsome golden boys, the image of the reserved and simple man who is on his way to an A is internal to this expressive medium, and it is not only emotional, but also emotional. atypical integrity. Like the rest of the great films Davis made between 1988 and 2021, the latest work from this voice, high, slow and patient of death, opens up questions about time and memory: in what direction does it flow?, how distinct is the past of the present, when the first one seems the most alive?, our first cinema present forever, how come memory and the past are finally separated?

Davis was born in the United Kingdom’s industrial belt in November 1945, just two months after the armistice in the Second World War. During the slow recovery of the post-war period and the traditional cruelty of oppressed Catholic families, they visited the huge popular restaurant halls, boutiques for thousands of hours, matinees and double programs to introduce themselves to a vitally different woman in the seared and hazy post-war style: the innocent and playful Hollywood of four and five years . Doris Day, Cary Grant, Rita Hayworth, Fred Astaire, Gene Tierney, Joan Crawford, Anne Baxter, Judy Garland. List of titles submitted to global search engine Sight and sound the past year, consisting mainly of classic industrialists of fifty years, shows the tenacity of this devotion, cultivated where I come from, to you, Singing rain (1952) in the popular film from Liverpool.

Diptych composed Distant voices th A long time ago (1992) needs to be rediscovered or re-examined as one of British cinema’s most idiosyncratic, sensitive and valiant debutante brothers who, after all, in the midst of an economic crisis and the shadow of Thatcherism, offered a menu of two unique characters at the time: the waxy anachronisms offered by James Ivory and Ismail Merchant, or the loud militant realism of the young socialists Ken Loach or Mike Leigh. None of the other traditions were strictly cinematic, but rather natural extensions of literary traditions widespread in the British imagination. In the middle, in that land of desert nadis, which has always been the avant-garde of cinema. The British who succeeded Derek Jarman and Peter Greenaway were distinguished by a healthy conceptual vandalism and intellectual density, but nevertheless remained close to popular taste.

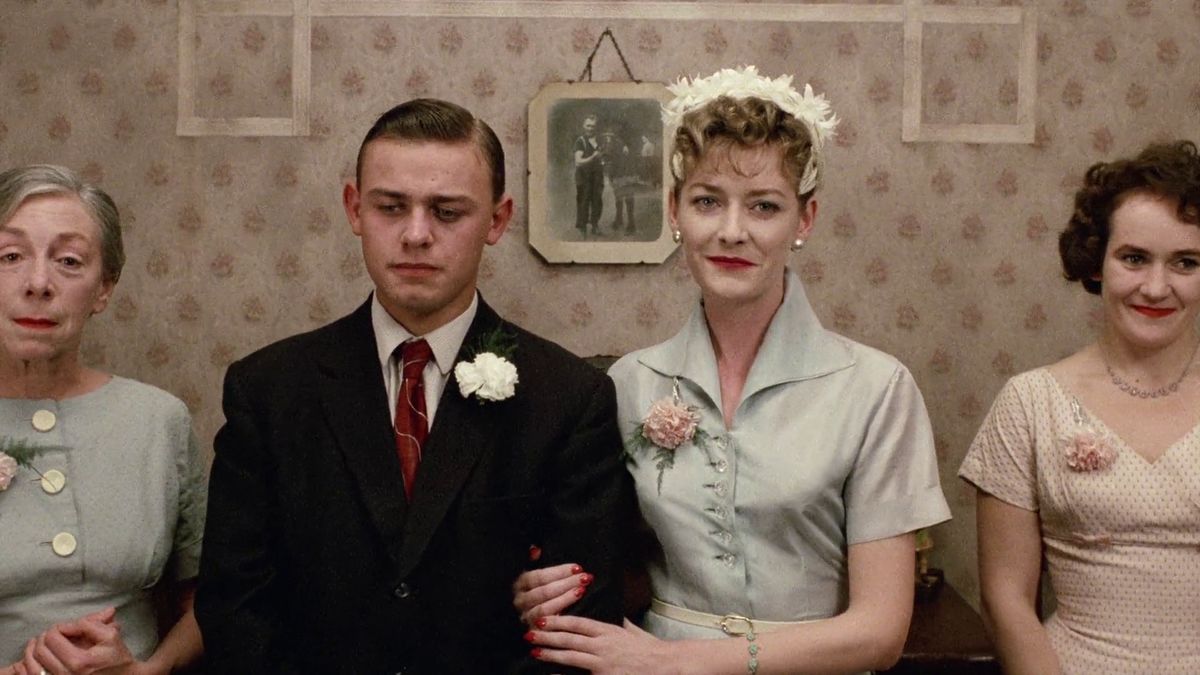

Photo Distant voices (1988), Terence Davis

Terence Davies was part of a British generation eager to imprint the war in their flesh and eager to join the punk wave three years later. His childhood was the same post-Belic and post-imperial legacy in which Martin Amis, Lennon, McCartney, Salman Rushdie or Roger Waters grew up. Davies seemed as iconoclast as the men mentioned above, but his revolution, described as low-key, intimate, in contrast to British cinema of the time, did not seem modern. Abbey Road (1969), until the ghostly echo of past times is forgotten.

Overall, over the course of seventeen years, Davis made many films of average length for free about those who, four decades later, radiated an inner life and emotion stronger than many of his contemporaries: Children (1976), Madonna and Child (1980) Death and Transfiguration (1983), Agrupadas después como The Terence Davies Trilogy (1984) are thousands of workers whose childhood and personal past are remembered not as nostalgic ghosts, but as a living, tangible presence. Yes, Richard Brody reported this New Yorker that Davis has been wrongly perceived as a director living in the past, when it is the past that lives in him as a continuous present, but his creative vision is impossible in the añoranza of the lost until there is a mysterious distance separating the two We. there were people today on the recording.

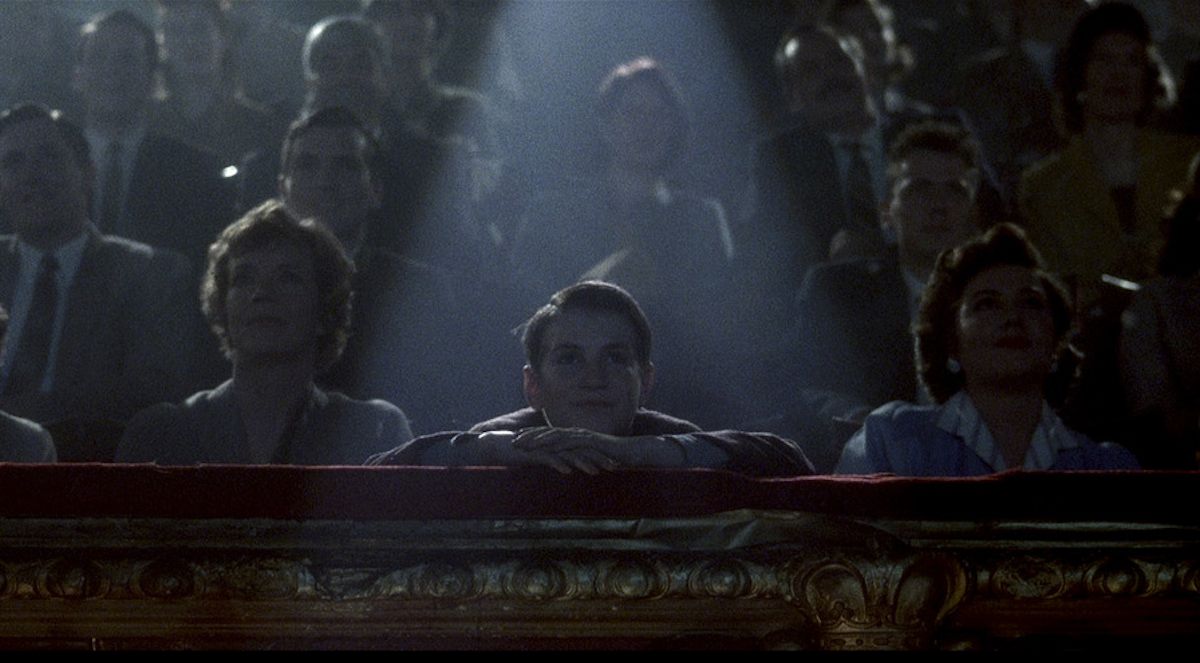

Photo A long time ago (1992), Terence Davies

In his filmography, which consists only of new feature films and four short films in recent years, Terence Davies has not included a single film either in the present or in the future. All of these are partially fictional reflections on the past of one’s own life, broken down by code biographical film – Emily Dickinson (Restrained passion 2016) or Siegfried Sazon (blessing2021)–, respectful literary adaptations –House of Joy (2000), Neon Bible (1995) or Atardeser’s Song (2011), starting with Edith Wharton, John Kennedy Toole and Lewis Grassic Gibbon respectively, or theatrical versions as Deep blue Sea (2011) – about the story of Terence Rattigan. Because it was precisely this seeming academicism of the filmmaker, retreating and hiding from the traditional forms, “prestad” of others, that gave rise in criticism to the bias of the solemn filmmaker and mannerist elegance, far from the sensitive experimental authors of the beginning of his era.

It is enough to refer to your filmography to dispel this misconception. Terence Davies’s melodrama, from the mayors to the restrained, always ends with a passionate and lucid rewriting of the themes that occupied its author. Like the common place in Flaubert, the invisible but omnipresent author in his work, Davis’s cinema, starting with Neon Bible It was a virtuous exercise by an author able to hide the depth of devotion—well explored by Almodóvar—to his actresses and female characters: the engaged women Gena Rowlands, Gillian Anderson, Cynthia Nixon, Rachel Weisz. Of all these and her striking works lower in the guide, Davis might say “Madame Bovary soy yo.” Yes, in fact, that’s how it was.