It may not remain in the public memory as indelibly as the coal pile that razed Aberfan Primary School in 1966, the fatal crush at Hillsborough Stadium in 1989 or the Grenfell Tower fire in 2017 Imagination. But the scandals of the 1970s and 1980s, when thousands of people around the world were transfused or injected with blood or blood products containing deadly viruses, have captured our imaginations as much as those better-known tragedies. Attention and compassion.

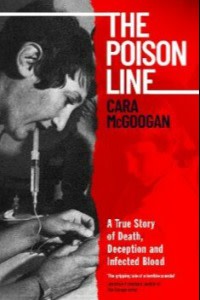

Although I was familiar with the broad outlines of the story until I read Caroline Wheeler’s death in blood with Carla McGugan poison line, I failed to realize the depth of deception and true evil that led to the infected bloody brutality and seeped into its aftermath. Both books make clear that this is a saga of government indifference, professional malfeasance and business greed.

Doctors experimented on susceptible hemophilia patients in their care without their knowledge or consent; pharmaceutical companies offloaded blood products they knew carried deadly viruses to countries that prioritized low prices. In the 1980s and 1990s, when legal developments in other countries seemed to raise the possibility that Whitehall officials might be held accountable, records that could be important for key decisions made by the British government were mysteriously destroyed.

When the Conservative government of the early 1990s agreed to pay some victims small compensation payments, they had to agree to waive future legal claims related to their infections, despite the fact that many had already been diagnosed with hepatitis C. But it was withheld until they signed.

Similarity of material, even some of the same anecdotes and overlap dramatis personae, a direct comparison of the two books can be made. It’s a tribute to McGugan’s smooth writing, in-depth reporting and ambitious revelations. Wheeler’s prose is bland by comparison, and his book focuses primarily on Britain – lacking McGugan’s international perspective on a scandal that rippled across multiple countries.

However, once it’s on track, death in blood Wheeler’s long association with the story enhances its grip. More than two decades ago, in the early weeks of her journalism career, a chance call from the newsroom of a Birmingham-area newspaper led her to meet a man who was living in fear of receiving infected blood and A man with an uncertain prognosis.

Over the next few years, as Wheeler’s career rose to national championship status, she became not just a chronicler but a protagonist, playing a key role in the public inquiry that was eventually approved in 2017. Her account is particularly powerful in revealing the truth and unforgiving detail of how doctors who were supposed to protect and care for hemophilia patients inexplicably agreed to use them as what she calls “unwitting human guinea pigs” to test treatments.

The setting for these experiments was Treloar Boarding School for disabled children in Hampshire. Wheeler writes that one of the “chief antagonists of the article” was Dr. Arthur Bloom, who at the time was considered one of Britain’s most eminent hematologists. In a letter from 1982 uncovered by activists, Bloom made clear his intention to give the product to previously untreated people to control bleeding because “previous test subjects – in this case, chimpanzees – No longer sufficient to ensure quality control” The manufacturer of this therapy is called “Factor 8”. It has been called “cheaper than chimpanzee” letters.

McGugan reports that former Treloar school principal Alec Macpherson was asked during the infected blood inquiry whether the school should have more surveillance. If doctors failed to act when they knew infected blood was used, “that would be negligence and a mistake,” McPherson said. But he added: “(F)or us in the school. . . . “We don’t have any authority. or reason to interfere. “

Some medical records are missing from this saga, but one chilling statistic caught me off guard: In the 1970s and 1980s, almost 10% of people who contracted HIV through contaminated NHS blood products One third are children. By the end of the book, readers are eager for Bloom and the other obviously guilty doctors to be held accountable. In fact, he died in 1992, many years before the public inquiry began to bring justice to the victims. Two other doctors who could have shed light on the incident were deemed too old to testify.

Wheeler focuses on the British victims of the tragedy as well as British politicians and Whitehall officials, while McGugan opens with a vignette that takes readers directly to the source of the infected product, a notorious building in Louisiana, USA. A notoriously grim prison. Here, inmates, including drug addicts and others at high risk for hepatitis and AIDS, are paid to provide plasma. In a shocking passage, a former prisoner-turned-whistleblower testified that he “knew people who had gone yellow (from hepatitis) and then continued to donate. One method was to bribe people who worked at the plasma center with cigarettes” Prisoner,” McGugan wrote.

The author shows a keen eye for poignant details. In the United States, a teenager with hemophilia lay dying on a mechanical bed in his living room. He was 5 feet, 6 inches tall when he first lay inside it, and when he left it for the last time, he was about 6 feet tall – “a teenager who was still growing even as he lost his life.”

It is certainly impossible to imagine that today’s patients might remain unaware of a major medical diagnosis for years, as many people with hemophilia and others do after contracting HIV or hepatitis C. But even if things get better in some cases, these books do little to reassure people that if the country chooses to come together, something like this will not happen again. This extremely shameful incident would never have been brought to light were it not for the bravery of a community whose members continued to fight for recognition and awards despite their failing health.

As McGugan points out, some countries are much quicker than others in making their reckoning. In the 1990s, France imprisoned a senior hematologist who gave McGugan a revealing interview and insisted the case against him was fabricated. In Japan, a financial settlement was reached with the victims as early as 1996; the head of a pharmaceutical company involved in the case made a confession on television.

In Britain, however, the wait is painful. It comes just over a week after the judge leading the country’s public inquiry, Sir Brian Langstaff, revealed that his final report, due to be released in the autumn, had been postponed until March – bringing with it a wave of scrutiny of the country’s public inquiry. Victims living off money also have little hope of quick compensation. time. Despite the best efforts of Wheeler and McGugan, the final chapter of this sorry story remains unwritten.

Death in Blood: The Inside Story of the NHS Blood Contamination Scandal Caroline Wheeler, Title £22, 400 pages

The Poison Thread: A True Story of Death, Deception, and Infected Blood by Carla McGugan, Viking £20, 416 pages

Sarah Neville is FT global health editor

Join our online book group on Facebook: FT Book Café