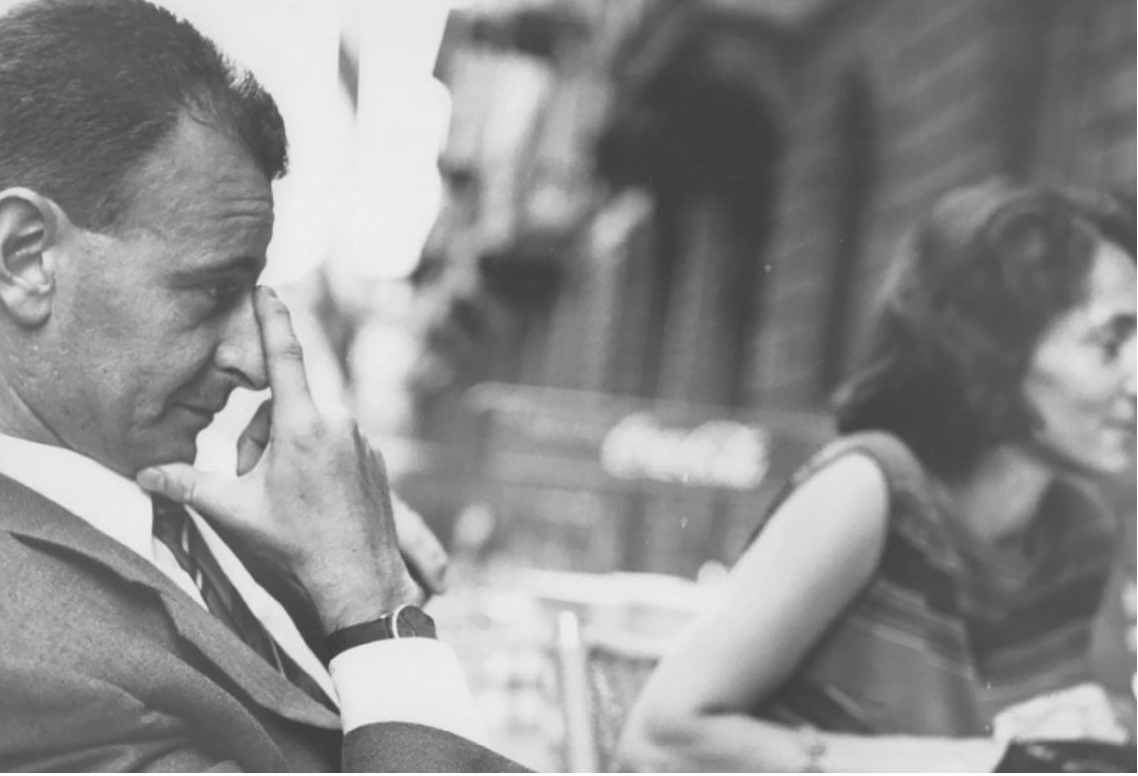

Collects a selection of over thirty years of interventions for HaKeillah, the glorious information organ of the Group of Jewish Studies of Turin, the volume “Being elsewhere. Writings on Judaism” (ed. Neri Pozza) by Emilio Jona. To fresco it an extraordinary wealth of themes and ideas which are also an opportunity for the author – born in Biella in 1927 and still a full-fledged protagonist of the cultural debate – to retrace the meaning and passions of a life. “I wrote these pages in my studio, in the heart of old Turin, in a welcoming house, with a neoclassical face, surrounded by the shelves of the library that collects my reading choices from 1945 to today, among the furniture that has been saved in our house in Biella Piazzo from the occupation and the havoc that the two Nazi officers who lived there made it”, he tells the reader before entrusting him with the summary of three decades of collaboration with Hakeillah. Among other things, a great expert of popular music, but also a lawyer and poet, narrator and playwright, Jona is a versatile and fascinating personality. With a multifaceted identity that makes him say he is “a secular, diasporic, atheist or rather religiously agnostic Jew”, but in any case aware of “the margin of mystery that surrounds us” and to whom Judaism is of interest “for its multiform realities, the reasons for the hatred that surrounded and surrounds him, his being based on the networks of memory, his relationship between memory and history, between the particular and the universal, the methodical doubt that accompanies him, his favoring the question over to the answer”. And again, among the various aspects on which he dwells, “being a thought of two rather than one, due to the relationship it creates with the text of sacred inspiration and the stratifications of its interpretations”.

Among other things, a great expert of popular music, but also a lawyer and poet, narrator and playwright, Jona is a versatile and fascinating personality. With a multifaceted identity that makes him say he is “a secular, diasporic, atheist or rather religiously agnostic Jew”, but in any case aware of “the margin of mystery that surrounds us” and to whom Judaism is of interest “for its multiform realities, the reasons for the hatred that surrounded and surrounds him, his being based on the networks of memory, his relationship between memory and history, between the particular and the universal, the methodical doubt that accompanies him, his favoring the question over to the answer”. And again, among the various aspects on which he dwells, “being a thought of two rather than one, due to the relationship it creates with the text of sacred inspiration and the stratifications of its interpretations”.

Interests which, according to him, did not lead him “to the center of Jewish thought or to a Jewish life”, but rather “to its peripheries, to a marginal and complementary Judaism”. From this perspective, a critical narration of other people’s texts “rather than my own vision of Judaism, which is perceptible only in the folds of my discourse,” emerges. A heterogeneous scaffolding supports the stimulating pages of this work. “Sometimes – explains Jona – what I deal with comes from important books, sometimes instead from marginal books, but it is always a matter of a detail that somehow communicates with the universal”. And of a thought that generally “is not univocal”, but double or interrogative. A thought, he underlines, “which assimilates the thought of others without ever being assimilated by it”.

“Being Elsewhere” is made up of eight sections. The first concerns more closely the issue of identity. In the second sub-investigation there are instead anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism, with a space for reflection dedicated to the “coordinates of prejudice” and the historical responsibilities of the Church in the construction of a certain imaginary.

Shoah and relationship with memory, German-Jewish dialogue, the future of the State of Israel, the Palestinian question: Jona has dealt with this and much more in his thirty years of collaboration with Hakeillah, whose headquarters – frescoed inside he beginning of the journey – “is Levi’s Argonopoli, that is, the once physically visible Jewish Turin that extended into a small quadrilateral of streets leading onto Piazza Carlina”. The voice, he argues, is “freer and more nonconformist than Italian Judaism where not only community issues have been debated (and are still being debated), but also those relating to Jewish reality and identity, anti-Semitism, Zionism, the Shoah , and the battles for democracy, anti-fascism and the secular state”. The collection of essays opens with a passionate defense of Diasporic Judaism in response to some critical considerations formulated by the Israeli writer Abraham B. Yehoshua, who was then beginning to have a certain following in Italy as well. Yehoshua, citing the Shoah on its merits, spoke of a failed experience with no future.

It was April 1992 when Jona, annoyed by that thought, wrote: “The Israeli Jew would not exist without the Diasporic Jew, who is his hidden part and in this case also misunderstood and denied”. It, he continued, “is his past, his memory, his critical conscience, his referent, and, whether we like it or not, also part of his present”.

Possible dialogue?

Two highly topical books have recently been published in France: Lettre à un ami juif (Ibrahim Souss, Flammarion, Paris 1988) and the response to it, Lettre d’un ami israélien à l’ami palestinien (Élie Barnavi, Flammarion, Paris 1988 ). Souss is the official representative of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) in France, Barnavi is a historian and political scientist, professor at Tel Aviv University.

Their topicality is given by the confrontation and the intense debate on some key themes of the Middle East conflict and by the sign that the recent positions taken by the PLO cast on it, which the two books precede, but of which they bear some premises and precise hints .

Souss’ book begins with a sort of ritual statement. It is obvious that in order to speak to one’s enemy one must first of all guarantee one’s back, make distinctions, precautionary premises and give assurances of good revolutionary conduct. There is therefore to begin with a well-found epigraph: “If they keep silent, the stones will cry out” (Luke 19, 40); then a second from René Char, French poet of the Resistance, on going forward and facing the pain inflicted by Hitler’s executioner; then a passage by Camus, taken from Lettres à un ami allemand: «No victory pays when the mutilations of man are without return», and finally, again

documentation of the non-innocence of the word, the affirmation that in the 1967 war Israel was not looking for the security of its populations, but for Lebensraum, the vital space of left memory.

First of all, it must be said that in reality Souss’ interlocutor is not Barnavi, but a Jew, not an Israeli, not even too intelligent and with a touch of fanaticism.

But that’s the way it is, they are to a certain extent forced paths of a certain Palestinian publicity, which is opposed, moreover, by an equally preconceived or mythological Israeli one. Barnavi does not feel these duties and has the advantage of speaking not to a figure of convenience, but to a real person.

However Souss, having chosen his own diasporic Jew as an interlocutor, having performed the due rituals, is now able to dialogue and to speak, he says, “the language of the heart” and of mutual respect to which Barnavi declares he wants to oppose another language, that of reason and politics.

For example, Barnavi wonders what Zionism is for Souss. Souss does not say it explicitly, but it is clear that for him it is a robbery movement, consciously carried out, devoted to the dispossession of the native populations.

There is in the mental and affective structures of every nationalist militant a basic incapacity to understand the nationalism of the other – says Barnavi – let alone when that other is the enemy. Now, that for the Palestinians

the Jews are intruders there is no doubt, and it is difficult for them to recognize the ancient thirst for Zion of the Jewish people, its torments as a pariah people, its desire for emancipation. However, one could at least expect recognition of the historical origins of Zionism, which can be found in the nineteenth-century idea of the national state and in the life-giving air that was breathed in that century, under the benevolent eye of Science and Progress, together with persistence of a multifaceted anti-Semitism of right and left, plebeian and bourgeois, cultural and social.

(February 1989)

James Debenedetti

Some time ago Renata Orengo, wife of Giacomo Debenedetti (Biella 1901-Rome 1967), one of the greatest, if not the greatest Italian literary critic of the twentieth century, told me that on the eve of his death Giacomino, as he was commonly called not only from friends, he had expressed with more determination his will to fulfill two old wishes: that of going to Israel and that of seeing Biella again, the place where he was born and lived up to 13 years. His death surprised him that he had already bought the plane ticket to Tel Aviv; as if the perceived imminence of the imminent end brought him back to his origins, the closest topographical ones and the most remote and profound ones of his Jewishness, a Jewishness apparently marginal, but nonetheless affirmed and accepted.

This brings up once again the problem of what it means to be/feel Jewish despite not attending the temple and not respecting the formal rules of the Mosaic law.

That memory came back to me while reading the book Giacomino that Antonio, the son, dedicated to his father and which is in the bookstore these days (Rizzoli, Milan 1999). It is a book of anecdotes, with many friendly faces and characters, many Jews or half-Jews. Half-Jews, on the other hand, says the author, quoting Saba, are Jews twice as much because they see themselves as Jews even through the eyes of their Aryan half.

But in addition to anecdotes and curiosities, it is a book of painful affections, of reticence, of ancient grudges and regrets because it is difficult to write about one’s father, especially if he is so important and cumbersome, even in his apparent inactions and in his reality of despotic , neurotic and revered parent.

We can now, with the help of this son, look at some aspect of Debenedetti’s Jewishness. He sees them, above all, through his mother’s eyes, in that sort of mixture of Jewish pessimism, in the mornings of his difficult awakenings, understood as something where Proust, psychoanalysis and perhaps even circumcision are mixed together.

But as for many Jews, remember Améry, the impact with the racial laws will throw his diversity in his face, and what was once an unnoticed or marginal fact suddenly becomes tangible and essential. And his reaction is one of disdain and pride: «an armor of apparent pride and eccentricity defends him» says his son «from the pain of having to hide his name at the bottom of those writings which are the primary, if not the only reason for his existence ».

(December 1999)

Political Zionism, cultural Zionism

Re-reading Theodor Herzl’s Der Judenstaat (1896) is a good exercise and a good start for reflecting on the themes that we are still debating on Jewish identity, on the relationship between Israel and the diaspora, on the interweaving of politics-society and religion, on reality and topicality of the Zionist movement.

David Bidussa republishes it, editing a selection of essays, with the title Political Zionism (Unicopli, Milan 1993) and introducing a broad introductory essay. When Herzl proposed setting up a Jewish state, he declared that he was driven by a universal necessity, by a driving force that exists in reality: Jewish poverty. Jewish misery was an anachronism in the realm of technology and Enlightenment culture, but anti-Semitism was stronger than enlightenment and progress, explicit or disguised as it was, it stood behind every social class; religious hatred had been its source, but now its spring was in the consequences of emancipation, in equal rights that could no longer be denied, so persecution spread while the Jews assimilated, or remained a people, that is, a historical group of members of a single family; and this made them, as in the past, an enemy. Therefore, the Jew had no choice but to discover his own strength, which was that of establishing himself as a state. The plan, said Herzl, is “extraordinarily simple”: “give us sovereignty over a piece of the earth’s surface sufficient for the just needs of our people and we will take care of the rest ourselves”.

Modern anti-Semitism for Herzl did not destroy but strengthened the Jewish group, causing marginal and emancipated Jews to fall into assimilation and making the most numerous and strongest nucleus of Judaism, that of Eastern Europe, more aggressive. Bidussa rightly points out that in Herzl’s project the problem is the Jews in the flesh, while there is no foundational conception of a theological or cultural nature of Judaism. Der Judenstaat is an “arid” text, apparently devoid of cultural depth, but perhaps its greatest simplification was its great communicative power, which made it the founding text of Zionism.

(June 1993)